Shadows on the Ledger

Digital money, vanishing identities, and the invention that came too soon

This is the second in a series exploring the hidden history of crypto: where it came from, who shaped it, and the systems of power it sought to subvert.

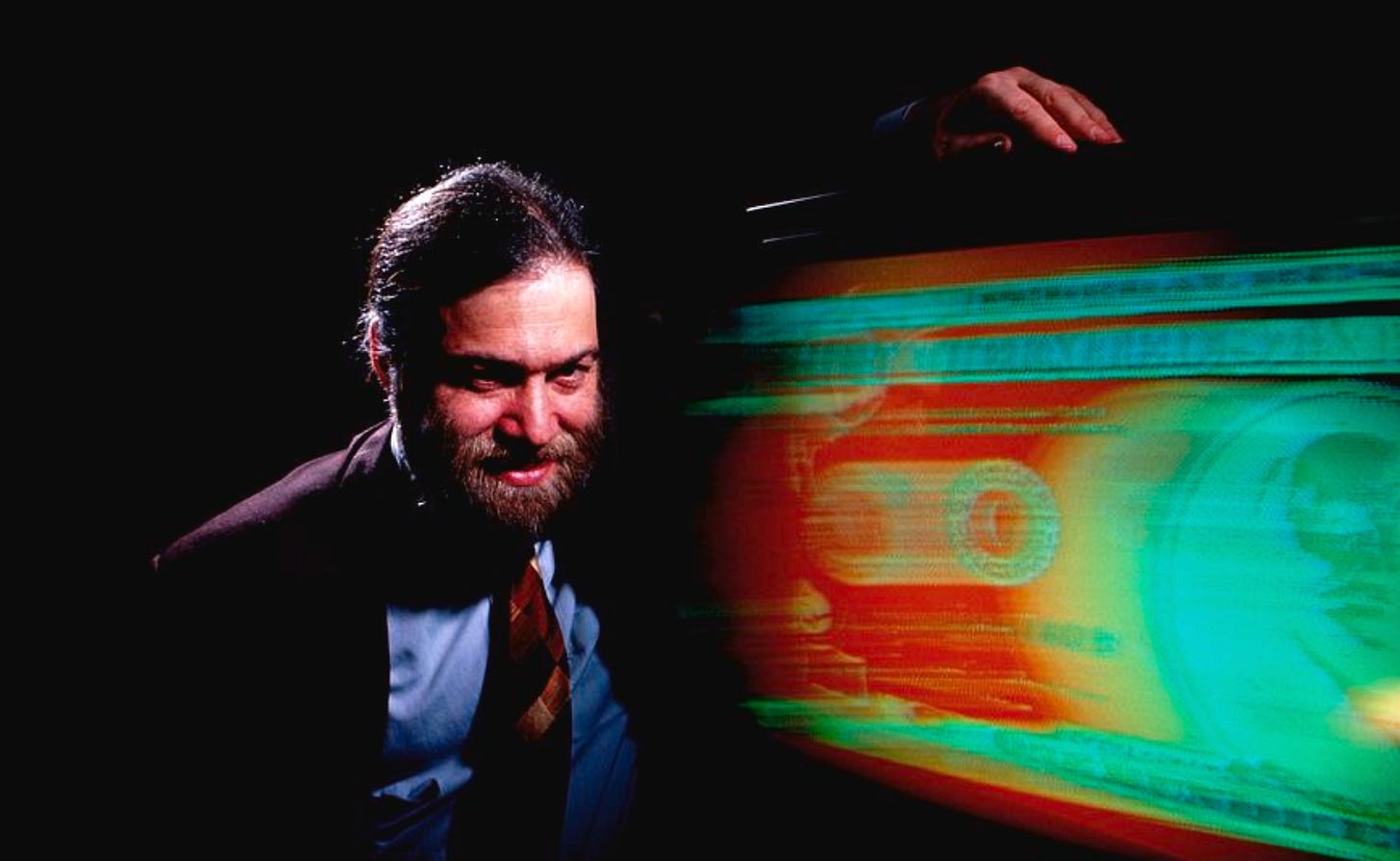

In the early 1980s, a young computer scientist named David Chaum began warning that digital records could be used to track everyone, everywhere, all the time.

Few listened.

At a cryptography conference in 1981, he stood up and said:

‘Computerisation is robbing individuals of the ability to monitor and control the ways information about them is used.’

Two years later, he proposed a solution: untraceable digital cash. It would use cryptography to make online payments anonymous, just like handing over physical banknotes. The concept was brilliant.

But it was also terrifying.

Origins of an idea

David Chaum was not a typical computer scientist. Raised in California, educated at Berkeley, he was equal parts engineer and political philosopher. From the start, he believed that privacy was not just a technical feature, it was the foundation of freedom.

In his 1981 paper, Untraceable Electronic Mail, Return Addresses, and Digital Pseudonyms, he introduced the concept of mix networks: systems that could break the link between sender and recipient. This wasn’t just about email. It was a warning. Communication in the digital age was becoming dangerously transparent.

Chaum saw it earlier than most. And he feared what was coming.

He worried that the same networks designed to connect people would also be used to surveil them. That every message, every purchase, every identity could be logged, indexed, and controlled.

This concern echoed the anxieties voiced just five years earlier, when Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman published New Directions in Cryptography (1976). Their paper proposed the first practical method for secure communication without a shared secret. A way to decentralise trust. It broke the monopoly the state had long held on cryptographic tools. But it didn’t resolve the question of how individuals would remain private once everything — communication, identity, money — moved online.

Chaum stepped into that space.

Money on the move

The early 1980s were a time of economic transformation. Reaganomics, deregulation, and globalisation were reshaping markets. The first ATMs had appeared. Credit card networks were expanding. Money was going digital. Fast.

But no one seemed to ask what it meant.

The system was consolidating. Financial institutions were growing larger, more interconnected, more opaque. Privacy was being automated away.

At the same time, Cold War paranoia persisted. The same cryptographic tools that could protect citizens were still classified as munitions in the United States. The state feared encryption in the hands of the people.

And so, while Diffie and Hellman had shown how secrets could be exchanged, Chaum asked: what about money?

Exile

David Chaum was brilliant. But he was also difficult.

In the mid-1980s, he left the United States and moved to the Netherlands. There, he founded DigiCash, a company dedicated to realising his vision of anonymous digital money.

The system he built was elegant. It used a cryptographic technique called blind signatures, allowing a bank to sign a digital coin without seeing its serial number. The result: money that could be withdrawn and spent without revealing identity.

It was, essentially, digital cash. But with one key difference: no one could track it.

Chaum saw this as essential:

‘In the not too distant future every individual will have to decide whether to ensure their own privacy or accept its absence.’

But others saw danger.

Bankers were wary. Regulators were confused. Governments were nervous. DigiCash struck deals (including Deutsche Bank and Mark Twain Bank in the US) but most collapsed. In 1998, the company filed for bankruptcy.

He did not work alone. Notable cryptographers like Stefan Brands and Amos Fiat collaborated on or extended his work, while a growing circle of cryptographic thinkers admired what he was trying to build. But support was scattered, and industry interest was tepid.

The biggest opposition was institutional inertia. Banks were already building compliance infrastructure. Regulators were shifting toward KYC frameworks. In that world, anonymous money was not just suspicious: it was unacceptable.

A solution no one wanted

Chaum had built a system that worked. But it worked in a way that no one wanted.

In an era before Bitcoin, DigiCash had everything: decentralised cryptography, privacy-by-design, a working product. But it was centralised in one respect. It needed a cooperating bank.

And banks did not want anonymity. They wanted compliance.

Chaum’s vision didn’t disappear. It dispersed. Future cypherpunks like Wei Dai and Nick Szabo would cite his work. So would Satoshi Nakamoto, whose 2008 Bitcoin whitepaper nodded to Chaum’s legacy.

Chaum was not a Cassandra. He was not ignored. His ideas survived. But they mutated—into something leaner, harder, more resilient. Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the decentralised finance movement that followed owed much to the ground he broke.

Privacy, power and the shape of money

Digital cash was never just about money. It was about the right to exist unobserved.

Chaum had seen the future: a world of constant surveillance, where behavioural data became currency, and privacy a luxury.

He proposed an alternative: technical, mathematical, incorruptible. But the world was not ready.

Instead, it chose convenience. It chose loyalty points. It chose cookies.

And so the infrastructure of surveillance capitalism expanded, unresisted.

The age of logging in

Today, we tap, click, swipe. We are told we are in control.

But every payment creates a trace. Every account, a dossier. Every login, a checkpoint.

We live in the opposite of what Chaum imagined. A world where identity is demanded at every turn. Where anonymity is criminalised. Where the burden of privacy is placed on the individual.

Chaum believed in systems that didn’t require trust. Systems that protected by design. We built the opposite: systems that say “trust us”, while logging everything. In 2021, he reflected:

‘People didn’t get it. I kept thinking, maybe they will. But they didn’t.’

But the future he described is no longer hypothetical.

It is here.

Bibliography

Chaum, D. (1981). Untraceable Electronic Mail, Return Addresses, and Digital Pseudonyms.

Chaum, D. (1983). Blind Signatures for Untraceable Payments.

Wired Magazine Archives (1990s). Profiles on DigiCash and David Chaum.

Green, M. (2015). A (Partial) History of Digital Cash.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

Interviews with David Chaum (various, 1996–2021).

Tim May, Crypto Anarchist Manifesto (1992).

Bitcoin Whitepaper (2008), Nakamoto, S.

Diffie, W., & Hellman, M. (1976). New Directions in Cryptography.